The benefits of staying small within large organizations.

Risk increases when initiatives get too big before they even start

For most companies, growth is too slow because decision-making is too cumbersome. This is especially true in marketing, where campaigns are undertaken as huge plans with lofty goals and multiple signatories. All the process aims at risk mitigation, but it actually increases risk and reduces reward, in large measure because the initiatives get too big before they even start. As a result, campaigns launch behind the risk-reward curve.

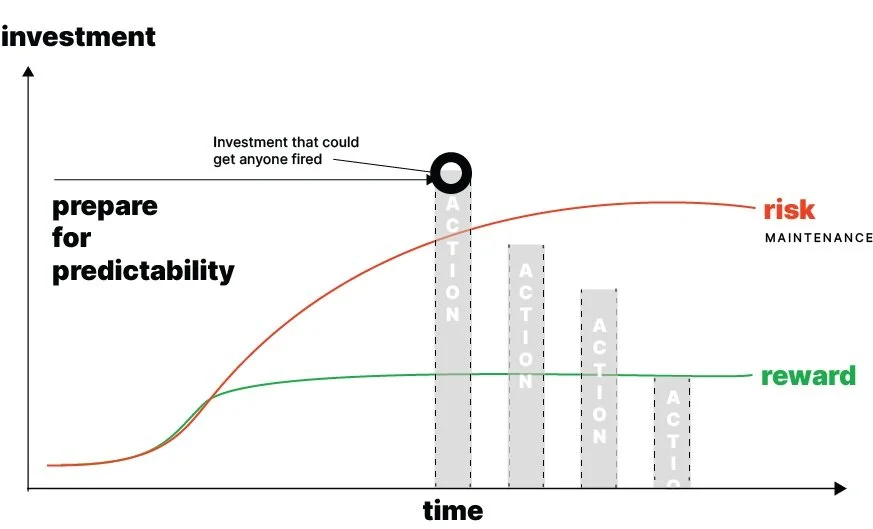

The charts here demonstrate this phenomenon. The so-called best-practice approach governing marketing (Figure 1) starts after everyone has signed off on a huge effort—one with stakes high enough to get them all fired—and then throws off progressively smaller efforts. Risk outweighs reward at the start, then eclipses it as the effort stretches over time.

Figure 1

By contrast, small efforts (Figure 2) when the risk-reward is even, then expand to bigger campaigns where the reward grows. They expand only because they're working, so the risk decreases and the reward increases as efforts scale.

Such small efforts are the model for effective marketing deployment that can inform the rest of corporate operations. In other words, Business needs a new orientation.

Figure 2

When an organization strives for predictability, it is actually seeking certainty. Yet certainty—like perfection—does not exist. Projects tilted at predictability are actually much riskier than projects designed for possibility. Striving for predictability creates a regressive, insular “bullet-proofing” of data that never ends.

Striving for possibility, on the other hand, creates a progressive, achievable, positive reach.

Possibility takes into account the larger realities that exist inside and outside organizations. “Would it be possible?” cannot be answered fully without real-world context. Such projects begin from a position of realistic accountability and reach. The more specific the possibility, the more achievable the project.

There is a sweet spot in all organizational endeavors that exists ahead of the curve—a time when risk and reward are both high enough to make it worth doing, but not high enough to draw the kind of attention that makes decision-making paralyzing.

It’s a point where possibility is still possible. If you miss this sweet spot, the project begins to grow in increased subjective importance that leads to exponential attempts to mitigate risk as the reward remains flat. Attempts to mitigate risk include, but are not limited to, spreading risk through decision by committee, increased individual strategies for plausible deniability, wait-and-see avoidance of commitment and quiet regression to the familiar status quo.

One potential sweet spot is when you’re gathering creative assets— often a box-checking exercise during which no one expects greatness. But if your team turns the footage, interviews and side banter into a prototype of what your organization can stand for, suddenly you have a vision, a strategy, a message and a fresh way forward. You’ve brought to life something that can inspire people without having to have it approved or scrutinized beforehand.

On the other hand, if you wait for help (more budget or people), you make it “official.” The subsequent flurry of emails and meetings puts you on the hook and steals your time. You miss your opportunity to prototype what's possible.

Effort expended at the sweet spot is in service of successful achievement of specific reward. Effort expended past this sweet spot is split between reward achievement and whole organization risk mitigation, with risk mitigation eventually eclipsing reward achievement, placing the organization behind the curve.

Return on effort at the sweet spot is 50% trending upward. ROE beyond the sweet spot is 0% trending negative.

Large organizations tend to move slowly and as a whole are physically set up to miss sweet spots and be trapped in an ongoing cycle of risk mitigation at the expense of reward. But smaller units within these organizations can see the sweet spots more clearly. The smaller the unit, the less risk carried against reward

Empowering the smallest viable units to achieve rewards autonomously can create a momentum of greater rewards throughout a large organization. Large organizations can then assess the most successful units and apply that learning across the other units to scale that reward momentum.

Predictability and certainty, like that other unachievable state, perfection, are all the enemy of good. It commonly takes 20% of an overall effort to complete 80% of a task, while completing the last 20% of a task takes 80% of the effort. Achieving absolute perfection may be impossible and so, as increasing effort results in diminishing returns, further activity becomes increasingly inefficient

Insistence on perfection often prevents implementation of good improvements. And making things better always starts with good.

This GCF-authored editorial originally appeared in Ad Age.